As Craft Breweries Grow, Employee Compensation Should Too

When the Farmer Series Pouring Permit was introduced in Massachusetts in July of 2013 it opened the door for the thriving taproom culture that dominates the craft beer scene here today. The change allowed all breweries to sell their beverages for on-premise consumption, a luxury previously afforded only to brewpubs. Less reliant on distributors, which often shave as much as 30% off the brewery’s bottom line, retail sales and profits soared for some of the state’s trendiest beer makers. Before long, these once-small operations found themselves with dozens of new retail employees pouring pints or selling takeaway beer for throngs of adoring fans.

In the case of a highly heralded brewery like Trillium, which annually produces upwards of 20,000 barrels of beer and sells nearly all of it straight to the consumer, that means millions of dollars in revenue. And though no one should begrudge them for being profitable, the recent controversy over their retail worker pay cuts has some consumers thinking less about new beer releases and more about brewery employment practices.

Given the considerable ethos that surrounds craft beer, it’s both surprising, and not, that its ardent supporters haven’t been more aware of how taproom economics impact both workers and consumers. In between penning glowing beer reviews and posting Instagram pics, perhaps we should all be wondering how much of the $15 to $22 per 4-pack we plunk down for hazy IPAs is being shared with its brewery’s workforce. Prior to the opening of its new brewery and restaurant, Trillium’s Fort Point retail staff (who neither poured pints nor provided samples) typically made $20 an hour, with more than half that coming from tips.

The job largely consisted of hauling cases of beer to and from storage, reciting their encyclopedic knowledge of the brewery’s many offerings to eager customers, and of course slinging lots of cans. But as consumer outcry revealed on social media and elsewhere, craft drinkers aren’t keen on tipping for takeaway beer at a fast growing and highly profitable brewery in order to ensure that its retail employees are fairly compensated.

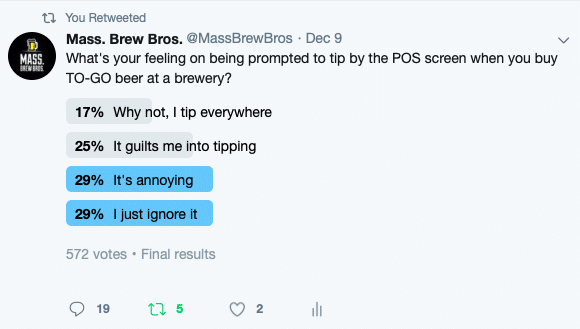

More than half the respondents who took part in our Twitter poll were either annoyed or felt guilted by POS screen prompts to tip on take-out beer.

At other New England breweries where patrons line up for highly sought beers at premium prices, retail workers are often hired at living wage rather than as tipped employees. The Alchemist and Hill Farmstead in Vermont pay hourly wages that range from $15 to $20 an hour, roughly equivalent to the price of their take-out beer. Others, like Lawson’s Finest (also in Vermont) or Allagash Brewing in Maine, not only pay competitive wages but actually donate all tips collected in their tasting rooms to charity. Allagash has also received awards for being an environmentally and socially responsible member of the community.

As a result of the public backlash, Trillium eventually reversed course and increased pay for retail workers to between $15 and $18 an hour, and stated that customers will still have an option to tip for exceptional service. The POS screen tip prompts were also changed from the previous 15 to 25 percent options to a more modest $1 to $3 range. In an interview with Craft Beer Business a week ago, Trillium founder JC Tetrault admitted that hanging out and enjoying beers in the taproom yields a different customer experience than buying beer to-go, and that their re-structuring of the retail process better reflects that now.

When hearing news of rapid growth and expansion, such as the case with Trillium’s meteoric rise, many craft consumers expect that workers’ pay is rising at a commensurate rate with brewery profits.

Within the industry, and Massachusetts is no exception, brewery business models and employee compensation packages vary. With the exception of Trillium and Tree House, both of which have retail staff dedicated primarily to their high volume takeaway sales, practically everyone else relies on a more traditional taproom hospitality model. Fast-growing Wormtown Brewery recently raised its minimum wage for full-time brewery workers to $15 an hour according to a story in the Worcester Business Journal. Managing Partner David Fields said that taproom staff, many of whom are part-time, are hired at $9 an hour as service employees, but make considerably more with tips.

Others that have enjoyed rapid growth include Jack’s Abby in Framingham and Night Shift in Everett. At Jack’s, which has a restaurant and a beer hall, all non-management employees are paid under a tipped-worker structure that pools gratuities and then divides them among staff at the end of each shift. The job entails a set of rotating service responsibilities that include some time in the retail shop. Night Shift declined our request for comment on its practices, but in a recent interview discussing customer complaints about beer prices in Massachusetts, founder Rob Burns said that as Night Shift pursues growth it also has to balance taking care of its employees with the cost of operating in a market like Metro Boston.

Related: Why The State’s Newest Craft Brewery, Redemption Rock Brewing, Is Donating its Taproom Tips to Charity

As craft beer sales have climbed, so has the industry’s impact on local jobs. Four years ago Harpoon faced a decision that had implications for its sizable workforce. With one of its founders looking to cash out, the region’s largest brewery declined a number of buyout offers from strategic and private investors and opted to convert 48 percent of the company to an employee stock ownership plan or ESOP. The move allowed the brewery to maintain its independent status while sharing minority ownership with its workers.

More recently at Democracy Brewing, which opened this summer in Boston’s Downtown Crossing, founder James Razsa took it a step further, opening the first worker-owned brewery in the state. Also a restaurant, all of its service employees are guaranteed $15 an hour (including tips) for every shift, or the brewery makes up the difference. Additionally, after one year of successful employment every worker is allowed to purchase a $3,000 class A share that entitles them to an equal share of the profits and an equal vote on any business decisions. Razsa pointed out that worker buy-in can even be financed, and admitted that he didn’t think the model would do much for the brewery’s bottom line, but said it was something he and his partners believed in.

Admittedly not every brewery is in a position to pay its employees what some of the big players do. And depending on their retail model or location, they may not need to. But if they experience significant growth, especially now that consumers are paying closer attention to industry employment practices, they would be wise to share some of those profits with the talented and loyal workers who help them prosper. It’s a competitive beer market out there, both in quantity and quality. If local breweries want craft drinkers to “buy local,” they need to show them how it benefits their local economy.

As writer Jeff Alworth recently observed in his Beervana blog: “If a brewery preaches an ethos that craft beer is different, that it’s about community and connection, then it will be held to that standard.” And if not all breweries measure up to that standard, many consumers are prepared to spend their craft beer dollars elsewhere. ![]()